Ted Huggins, Central Anchorage and Towers, San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, August 1934

California Historical Society

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the opening of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. In celebration, we offer this account about an intrepid photographer and his images of the bridge during its construction (1933–37).

Inspired by the photograph above, the following essay originally appeared as the Spotlight feature in California History (vol. 93, no. 4). The author has further illustrated it to provide a visual sense of time and place in the story of the bridge.

By Shelly Kale

“The Titan of Bridges” is how Popular Mechanics Magazine described the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge in January 1933 as it neared the start of construction. Nearly four years later, at opening ceremonies on November 12, 1936, former president Herbert Hoover, an engineer himself, recognized the new bridge as “the greatest bridge yet constructed in the world.”(1)

Like the Golden Gate Bridge to the north, the Bay Bridge was built in the throes of the Great Depression. Providing work for thousands of laborers, the two gigantic bridge projects connected San Francisco with communities across San Francisco Bay, boosting the economy of the region, unifying it, and preparing it—perhaps prophetically—for the population explosion and transportation needs of the postwar years.

Line-up in front of “The Kitchen,” San Francisco, c. 1930–31

Courtesy San Francisco Chronicle; photo by R. Hass, Jr.

Both bridges faced engineering challenges. With a Depression-era “can-do” spirit and an ingenuity “never before demanded in bridge construction,” bridge designers overcame the obstacles presented by the bay. Addressing water depth, strong tides, fierce winds, and the long span lengths required to connect the city with its northern and eastern neighbors, they actualized a decades-long dream of bridging the bay. (2)

Aerial View of Oakland, California: Oakland Harbor Areas, c. 1930

Courtesy Library of Congress

Approximate Location of Bridge across the Bay, c. 1933

Popular Mechanics Magazine (January 1933)

Both bridges were, in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s words, “marvels of the century.” At the time of its completion, the Bay Bridge—at 8.4 miles long—was the largest and most expensive steel bridge ever built; the Golden Gate Bridge was heralded as the longest suspension span in the world, at 4,200 feet. (3)

And both bridges were photographed under construction by an amateur photographer who—with innovation and diligence, and at personal risk—chronicled history in the making. A public relations executive at Standard Oil Company of California (or Socal, now Chevron), Theodore (Ted) Huggins (1892–1989) recognized the significance and impact these “symphonies in steel” would have in the Bay Area, across the region, and throughout the state. (4)

A Split Second

Huggins photographed the bridges from 1933 to 1937, when “the heroic age of American bridge building” was at its peak. His journals record his many bridge outings at all times of day and night and the occasions on which his publicity photographs were published locally and nationally. With a 3A Kodak, a $100 Rollieflex camera, and a $60 infrared Recomar camera, and with company planes at his occasional disposal, Huggins captured all facets of bridge construction, with images ranging from underwater to aerial shots. As his daughter Carol Huggins Trabert recalled, “My father scrambled all over, up and down cables, in construction buckets. . . . He took thousands of pictures.” Huggins was in good company: many renowned photographers of the day aimed their cameras on the bridges, including Peter Stackpole, George Dixon, and Gabriel, Irving, and Raymond Moulin. (6)

Ted Huggins, Construction of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, East from Yerba Buena Island, c. 1934–35

California Historical Society

Ted Huggins, Construction of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, Eastern Span, c. 1934–35

California Historical Society

California Dreaming

Huggins had been a proponent of the Bay Bridge since 1923—“my dream of 10 years ago,” he wrote in 1933 as construction began. He actively pursued civic and public agencies connected with the bridge on behalf of Socal, whose petroleum products were used “for utmost mechanical efficiency” on both bridges. He was committed to the growth and prosperity of the region and was an integral part of planning for its future. He was one of the first—if not the first—to propose the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. (7)

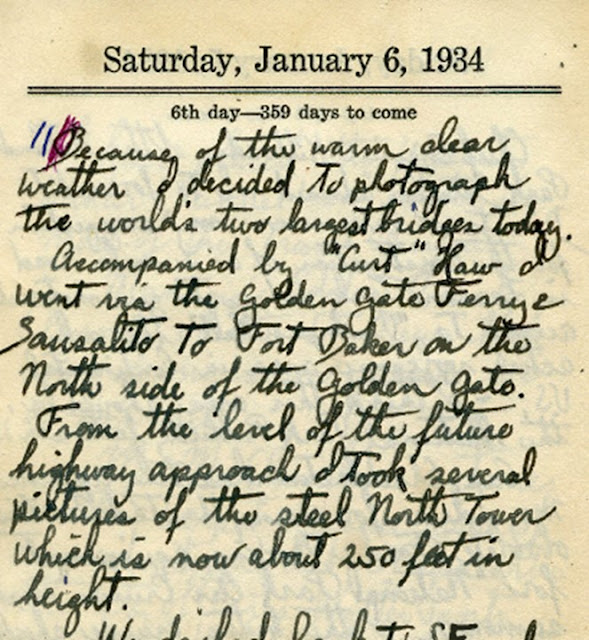

Ted Huggins, Diary Page, January 6, 1934

Courtesy John C. Harper, Chevron Corporation Archives

In 1934 Huggins wrote with great satisfaction on the progress of the Bay Bridge:

Mar 7. A milestone in the history of the Bay Bridge—that structure that I started to promote just about 11 years ago and which efforts for a 2 or 3 yr period were ridiculed by most people who said “It can’t be done—it’s too big a job.” But today the first steel erection was commenced—on Pier 2 at the outer end of Dock 24. It makes a grand sight from my office window. (8)The enormity of the bridge’s construction also was not lost on the public. Numerous publications brought the task to a scale a layperson could understand. As one author noted, “The principles involved [in suspension bridge construction] are probably the most difficult to grasp.” Popular Mechanics Magazine explained: “Enough concrete for forty Tribune towers will go into the Bay Bridge”; “For the cables of the bridge enough wire will be used to go around the world three times”; and “The Bay Bridge requires enough steel to build twelve battleships.” Standard Oil Bulletin offered: “Thirty-five full moons would be able to equal the average intensity of the artificial light” on the bridge’s upper deck.” (9)

Cover, San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge: A Technical Description in Ordinary Language

(San Francisco: E. Cromwell Mensch, 1936)

How to Use the New Bridges (Standard Stations, Inc. and Authorized Distributors, c. 1937)

Courtesy John C. Harper, Chevron Corporation Archives

Creativity and Innovation

Writing on February 20, 1934, about that art deco masterpiece, Huggins described one of his photographic adventures:

Clay Bernard of the Golden Gate Bridge District took Frank Vail, Universal News Reel cameraman, and myself to the Marin Tower. First we photographed scenes from the “cage” as we were pulled up midway between the columns almost to the Top of the Tower. After lunch we climbed on a railed platform 10 ft square and were hoisted by the boom on the traveler to a point 30 ft above the Top of the Tower, or elevation 550’. It was a unique, thrilling experience which I recorded on 22 photos. (11)

(Detail) Ted Huggins, Central Anchorage and Towers, San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, August 1934

California Historical Society

Six months later, on August 23, 1934, Huggins made the Bay Bridge photograph that is featured in this essay [detail above]. “With a bridge engineer and another correspondent,” he wrote, “I inspected the SF-Oakland Bay Bridge.”

We took pictures at the Central Anchorage which now has its bottom concrete seal. Then we went to the “stepping-stone” nearest the [Yerba Buena] Island where I took more pictures. East of the Island we stopped at the caisson 1400’ from its shore. It has been sunk deeper than any other in the world, 183 ft. below the surface, I think. Our next stop was at an open excavation pier. . . . We gazed upon workmen spreading concrete about 50 ft below the water-level. Finally we stopped at the end of the key fill and climbed up the bridge’s 1st steel span. (12)Huggins’ enthusiasm for his bridge work carried into his publicity campaigns and speaking engagements. Just a few years before his retirement from Socal in 1957, he addressed the Lions Club at Lodi, California, on the myriad uses of petroleum. The Lodi News-Sentinel reported on his humorous presentation of a “Magic Barrel” of petrochemical products: “Huggins introduced his show in a manner slightly remindful of Gypsy Rose Lee—only slightly because he is a somewhat baldish male. He stripped off various articles of clothing to demonstrate what can be done by combining crude oil with chemicals, retaining just a few essential garments.” (13)

This inherent flair for theatrics no doubt reflected the creativity and vision that brought the Berkeley native’s images of the bay’s bridges to millions of people.

Ted Huggins (1892–1989) Explores the World in 1934 and in 1977, 1977

“Retire—For Fun and Profit!,” Standard Oiler (February 1977)

Notes

The author thanks John C. Harper, Chevron Corporation historian, for his invaluable assistance and for sharing primary sources from the Chevron Corporation Archives.

- Tom White, “The Titan of Bridges,” Popular Mechanics Magazine 59, no. 1 (January 1933), 13. Karen Trapenberg Frick, Remaking the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge: A Case of Shadowboxing with Nature (London: Routledge, 2016), 21.

- “Up Goes the Steelwork!” Standard Oil Bulletin (February 1935), 3–4. E. Cromwell Mensch, San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge: A Technical Description in Ordinary Language (San Francisco: Standard Oil Co. of California, 1936), 3.

- The American Presidency Project, “Message Opening the Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco,” February 18, 1939; http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=15716, accessed August 6, 2016.

- John B. McGloin, “Symphonies in Steel: Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate,” Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, http://www.sfmuseum.net/hist9/mcgloin.html, accessed August 8, 2016.

- Collections of Huggins’ bridge images are housed at the California Historical Society in San Francisco and at the Chevron Corporation Archives in San Ramon, California. Chevron Corporation, Picturing a Masterpiece—Ted Huggins and the Golden Gate, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-jgW0KnWUMQ, accessed August 5, 2016.

- Richard Dillon, Thomas Moulin, and Don DeNevi, High Steel: Building the Bridges across San Francisco Bay (Millbrae, CA: Celestial Arts, 1979), 6, 7. Ted Huggins, 1933 and 1934 diaries, Chevron Corporation Archives. Chevron Corporation, Picturing a Masterpiece.

- Huggins, 1933 diary. Standard Oil Company of California, Standard Oil Bulletin (February 1935), 7. John Harper, email exchange, August 10, 2016.

- Huggins, 1934 diary.

- Mensch, San Francisco Oakland Bay Bridge, 1. White, “The Titan of Bridges,” 13. Standard Oil Company of America, Standard Oil Bulletin (November 1936), 5.

- Allan G. Smorra, “Ted Huggins’ Split-second Decisions,” blog entry, December 2, 2012, https://ohmsweetohm.me/2012/12/01/ted-huggins-split-second-decisions/, accessed August 7, 2016.

- Huggins, 1934 diary.

- Ibid.

- “Petroleum Uses Told Lions Club,” Lodi News-Sentinel, February 18, 1954.

Shelly Kale is Publications and Strategic Projects Manager at the California Historical Society. Formerly Managing Editor of California History, she has held editorial and administrative positions in academic, museum, educational, electronic, and trade and mass-market publishing.

______________________________________________________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment