The Great Depression—Reclaiming the Good Life

|

| Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing |

|

| Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Co., 400-430 4th Street, San Francisco, c. 1937 California Historical Society |

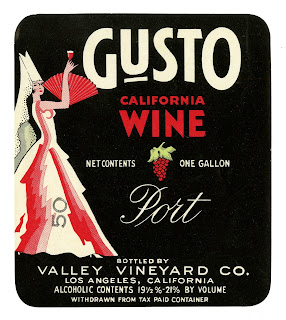

In their design, the labels—with recurring motifs such as parted curtains, heavy vines, and peaceful fields—combined Art Deco elements with romanticized references to the Middle Ages, the Mission Era, and the Gold Rush. Mythologizing both California’s past and present, they illustrated a vision of social and industrial harmony from which the bitter realities of history were excluded.

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

The Lehmann art department flourished in the fast pace of mass production, finding in their daily grind opportunities for seemingly inexhaustible creative invention. The firm’s inventive talent continued to shine in its extraordinary output of individualized labels. Yet even custom labels shared standard colors, backgrounds, and lettering.

Lehmann Printing Presses, c. 1937

California Historical Society

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

Owner Adolph Lehmann believed that a good label was the expression of an idea, conceived and executed with a specific purpose. In his labels, these ideas were expressed in motifs—such as the theater curtain and top hat; the chivalric knight and kindly friar; the heavy vine, peaceful field, and magnificent chateau; the race horse and yacht—whose purpose might be understood as the marketing of the California myth.

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

A beautiful and unsettling example is the Varsity Brand California Tokay label designed for Los Angeles’ Hollenbeck Beverage Co. Two framed vignettes show a padre blessing a kneeling Indian and an oddly modern-looking mission complex. These appear against a classic Lehmann manuscript background, decorated with orderly fields and a plump cluster of grapes, on which the incongruously collegiate brand name, Varsity, is printed in ornate Gothic lettering:

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Wine Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

In the mid-1930s Lehmann pioneered a stock label service, creating catalogs of generic labels with stock vignettes that could be applied to a wide variety of products. As his contemporaries observed, Lehmann’s labels were

“. . . labels of distinction, of artistic quality, created individually for the containers of products for which they are to be used. Fruit and vegetable packers of California and other states of the country recognize the Lehmann labels as being of superior grade, giving to their products an advertising value before the public which only an attractive label could insure; a label which impresses the buyer as having been conceived and executed for the particular food or delicacy which it names. . . . His labels have sold themselves; they have carried their own recommendation without the aid of extensive advertising or numerous salesmen.”

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Stock Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Company Stock Label, 1930s

California Historical Society, Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

In 1934 alone, orders from three large wineries totaled over $100,000 (nearly enough to cover the firm’s annual payroll). Even earlier, in 1931, the business community observed:

“A convincing estimate of the status of the Lehmann Printing & Lithograph Company is indicated in the splendid business reports during the days of so called depression of 1931. Among other figures, it may be mentioned that overtime in some weeks at present amounts to over one thousand dollars per week in wages, and the plant is operating every hour of the day. As a business it is one of the most notable achievements in San Francisco and on the Pacific coast.”

Boxing Labels, Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Co., 1937

California Historical Society

As one journalist began his observations in a 1935 issue of The Inland Printer:

“This is the story of a printer who hasn’t heard about the depression. He started in business in San Francisco in 1911, five years after the ‘fire,’ with a total investment of $190. His plant consisted of a 10 by 15 platen press and a few fonts of type. His rent was $10 a month; his staff, one boy.

“However, this printer had ideas. Today, twenty-four years after that small start, Adolph Lehmann is still the sole owner of Lehmann Printing and Lithograph Company. The first is worth $600,000 and an additional $100,000 is to be spent in the next few months on enlarging the plant and adding new offset and bronzing machines, and other equipment.”

Putting On Labels, Lehmann Printing and Lithographing Co., 1937

California Historical Society

As the wine industry slowly recovered following the repeal of Prohibition and during the Depression, Adolph Lehmann’s business rapidly progressed. Indeed, The Inland Printer saw Lehmann as a model for others:

“Sole owner of printshop says he wasn’t bothered by depression; his ideas, standards can guide you.”Marie Silva

Acting Director of Library and Archives

msilva@calhist.org

Shelly Kale

Publications and Strategic Projects Manager

skale@calhist.org

Sources

- Lewis Francis Byington and Oscar Lewis, The History of San Francisco, California (Chicago/San Francisco: The S. J. Clark Publishing Company, 1931)

- D. H. De Michaels, “Builds $190 Shop into $600,000 Plant; Tells Methods,” The Inland Printer (January 1935)

- Hillel Aron, The Story of Los Angeles/ 1932 Olympics, When Everyone Was Poor; http://www.laweekly.com/news/the-story-of-los-angeles-1932-olympics-when-everyone-was-poor-7251494

- Jonathan Rowe, Cooperative Economy in the Great Depression; http://jonathanrowe.org/money-cooperative-economy-in-the-great-depression

- Andrew F. Smith, ed., The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2007

_____________________________________________________________________________

Love California Wine and Spirits? Don’t Miss Our New Exhibition!

Vintage: Wine, Beer, and Spirits Labels from the Kemble Collections on Western Printing and Publishing

December 10, 2016–April 16, 2017

California Historical Society, 678 Mission, San Francisco