|

| Vin Scully at Dodgers Stadium / Courtesy of ESPN. |

If baseball is America’s national pastime, then veteran Dodgers announcer Vin Scully is the American Dream personified. He is so iconic that even the musician Ray Charles asked Bob Costas to introduce him to Scully after an interview in 1994. Today we will say goodbye to an internationally recognized sports broadcaster who feels like our kindly nextdoor neighbor. Fittingly, this last long goodbye will end during a Giants-Dodgers series just to prove that History often writes itself. The litany of tribute articles have been unanimously reverential, regaling us with the staggering career statistics of a living legend; more often than not, they’ve focused on authors’ personal stories because historic moments inspire remembrance, especially when we’re aware of their import in real-time. To this canon of compliments I’d like throw my own personal story into the mix, and thank you in advance for allowing a daughter the indulgence of remembering her father and the broadcaster that connected them.

|

| My Dad as a scrappy Pony League standout around age 14 in Arcadia, California c. 1963. / Courtesy of Nicole Meldahl |

Baseball was a given in my house as a kid. My Dad, Bob Meldahl, was a local Pony League legend, and old-timers would often recount me with tales of his glory...as well as stories of his misspent youth; my father was a lovable rascal. He tried to carry that talent to the next level, and briefly played baseball at Pasadena City College (just like Dodgers great Jackie Robinson) before he was forced to unenroll due to residential zoning restrictions. Like many before him, my Dad put aside his sandlot dreams to build an adult life, and he did alright for himself: eventually becoming a notable jockey’s agent, representing Laffit Pincay, Jr., and buying a classic Southern California ranch home where he watched his family thrive.

|

| My childhood cat, BJ, using Dad’s hat as a headrest (much to his chagrin). / Courtesy of Jan Meldahl. |

Through it all my Dad bled Dodgers Blue, even while my Mom and I pledged allegiances to the Anaheim Angels and the Atlanta Braves because of teenage crushes on Mickey Mantle and Chipper Jones, respectively. Much of my childhood was spent watching The Dodgers on KTLA or at Dodgers Stadium where my Dad seemed to know everyone because old-school Dodgers fans and stadium employees also played the ponies at Santa Anita Racetrack. When Dad got sick in 2009, we watched The Dodgers from his hospital bed as a family--my Mom, my Dad and me focused on the pitch count, thinking of the pennant race, and wishing for better times. Then, when we lost him in October of 2010, we placed a crisp new Dodgers baseball cap in his casket; ashes to ashes, dust to dust, my father was a Dodgers fan from the cradle to the grave.

The last time I set foot in Dodgers Stadium was with my Dad, but I didn’t stop listening to Dodgers broadcasts even after I did the Dodgerstown unthinkable and defected to San Francisco. Vin Scully was not only a touchstone of my childhood, he was a constant presence for my Dad’s entire life. Think about that: my Dad, a lifelong Dodgers fan born in 1949, never heard a Dodgers game that was not called by Vin Scully. A living link to the golden era of baseball, Vin Scully has been present for 87 of 94 World Series broadcasts, and has been a broadcasting participant in 22 of them. Managers moved on, owners gave up the ghost, and players peaked to become footnotes while one man sat in the Dodgers announcer’s booth (now named in his honor) for six decades. They just don’t make ‘em like Vin Scully anymore, nor do they make ‘em like my Dad.

|

| Vin Scully, c. 1934. / Courtesy of Reddit user TheBrimic. |

Vincent Edward Scully was born in the Bronx in November of 1927 to Irish immigrants Bridget “Bridie” (Freehill) Scully and Vincent Aloysius Scully. The Scully family lived in Washington Heights, and would take long walks on the Fordham Prep School campus Bridie dreamed her son could one-day attend. After her husband died of pneumonia in 1932, a grief-stricken Bridie took young Vin home to Ireland where she recovered amongst family. The pair returned to the United States, and Bridie married an English sailor named Allan Reeve who became a father-figure to Scully. To this happy family was born a daughter, Margaret, and just like that Scully became an older brother. He often recounts how he would crawl under the family’s radio with a plate of saltine crackers and a glass of milk to listen to college football broadcasts. With this in mind, he was certain of his answer to a school assignment asking students what they wanted to be when they grew older: Vin Scully was going to be a broadcaster.

During big moments in a game he listened to at home with his family, he would close his eyes and let the sound and resultant goosebumps wash over him. The effect that radio had on Scully cannot be underemphasized. NBC and CBS, networks with which Scully would later contract, were incorporated in 1926 and 1927, and the Radio Act of 1927 laid the foundations for the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Modern broadcasting as a federally regulated service began the year Vin Scully was born. When put into this context, you can see how incredulous a parochial school boy’s desire to become a broadcaster really was. His ability to paint what he sees on the field and his penchant for dramatic pauses, essentially the things that make him an unrivaled announcer to this day, can be attributed to his origins in and love of radio.

|

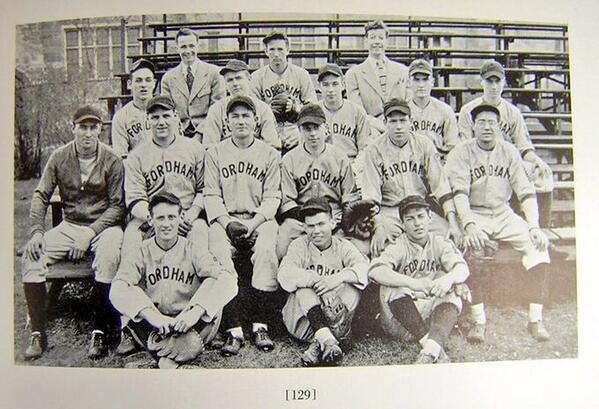

| Vin Scully with his Fordham baseball team, 1944. / Courtesy of Vin Scully. |

At Fordham Preparatory School in 1940 and later at Fordham University in 1944, Scully played center field for the school’s baseball team, the Rams, but he really excelled off the field. He sang with a barbershop quartet called the Shaving Mugs, studied elocution, and performed in plays--learning the intricacies of public speaking and entertainment. Most importantly, he covered sports for the Prep’s newsletter, the Rampart, and stepped into broadcasting at WFUV, Fordham’s radio station. After graduation, he began applying to smaller-wattage radio stations in the area. He eventually found work as a summer substitute at WTOP in Washington, D.C., and was able to meet Red Barber, voice of the Brooklyn Dodgers, through CBS news director Ted Church. When CBS was short an announcer for College Football Roundup that Fall, Barber brought in Scully to call the Boston University-Maryland football game at Fenway Park. Scully nearly froze calling that game because he failed to bring an overcoat, thinking he’d be inside the booth, but his dedication paid off--he was sent to cover the Harvard-Yale game the following week.

|

| Red Barber, Connie Desmond, and Vin Scully. / Courtesy of DodgersInsider. |

When Ernie Harwell left the Brooklyn Dodgers broadcast team, Scully filled his seat alongside Red Barber and Connie Desmond in 1950--ironic for a self-professed New York Giants fan who came of age at the Polo Fields. He began calling himself Vin instead of Vince (because “Vince Scully” sounded too lispy), and learned from Barber’s folksy Mississippi style. Barber also taught him not to imitate other broadcasters, to find his own voice, and to keep his distance from the players in order to maintain his objectivity. By 1954, Barber had left and Desmond’s drinking had become problematic so Scully and Jerry Doggett were made primary announcers for the Brooklyn Dodgers.The next year he became the youngest person to broadcast a World Series game, calling the Dodgers’ first and only championship at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn in 1955.

|

| Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett, 1965 / Courtesy of the Los Angeles Dodgers via The New York Times. |

His career in Brooklyn was taking off, but Scully’s time in New York was about to come to an end. In 1956, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley was frustrated by stalled negotiations with the City of Brooklyn over the construction of a new stadium. When the City of Los Angeles offered O’Malley land for purchase in the Chavez Ravine, as well as complete control over the stadium’s revenue, he decided to move his team to California. O’Malley also convinced New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham to move his team to the west coast, thus keeping intact a lucrative rivalry with roots in the 19th-century. Both teams went west after the 1957 season, much to the delight of Californians north and south, but the Dodgers’ stadium was still under construction so the team opened the 1958 season against the newly relocated San Francisco Giants in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Built for the 1932 Olympics, the Coliseum was a giant stadium not well-suited to watching baseball, but it became a boost to Scully’s popularity.

|

| 1959 World Series at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. / Courtesy of Wikipedia. |

Vin Scully was determined to connect with his new base of Los Angeles listeners. He worked hard to highlight “rank and file” players, not just the superstars, by reading media guides, newspapers (local and from opponents’ hometowns), and magazines to find engaging stories--a process he calls “searching for seashells.” He has done this throughout his entire career, filing this information away in cabinets and using it to seed his conversational style. Luckily, the development of portable transistor radios enabled fans to bring Scully with them to the ballpark, and his narrative of the action compensated for their distance from the field of play. The same technology allowed Los Angeles residents to listen to Dodgers games in their backyards, at the beach, and in the car. Scully worked hard to craft content, and that content was disseminated not through television, which O’Malley was still hesitant to adopt, but through a cheaper, far more accessible, means of transmission. Once again, advancements in radio technology were perfectly timed to further Vin Scully’s career.

|

Aerial view of Dodgers Stadium in the Chavez Ravine (detail), 1962. / California Historical Society at USC Special Collections.

|

And what a career it’s turned out to be. Since it opened in 1962, Vin Scully has been calling games in Dodgers Stadium, now the third-oldest in Major League Baseball. Danny Kaye immortalized him and the team’s rivalry with the Giants in song with “D.O.D.G.E.R.S.” that same year. He was earning more than most of the team’s players, and for good reason, by 1964. Scully is meticulous, a fact visible in his attire and seen in the phalanx of source materials at his desk in the announcer’s booth. Typically at his disposal are two media guides, home and away, stuffed with index cards filled with personally prepared notes. He has a blue pen to make corrections, a red pen for pitching changes, and a yellow highlighter for come-what-may. His pockets are filled with Jolly Rancher candies in case his throat gets dry, because liquids are a broadcaster’s worst enemy; baseball does not pause for bathroom breaks. Over the years, he’s developed a signature style now emulated in announcer’s booths around the world. He approaches announcing like a casual conversation, and treats listeners not like fanatics, or fans, but like his friends.

“My idea is that I’m sitting next to the listener in the ballpark, and we’re just watching the game,” Scully said. “Sometimes, our conversation leaves the game. It might be a little bit about the weather we’re enduring or enjoying. It might be personal relationships which would involve a player. The game is just one long conversation and I’m anticipating that, and I will say things like ‘Did you know that?’ or ‘You’re probably wondering why.’ I’m really just conversing rather than just doing play-by-play.”

|

| Kirk Gibson at the plate on that fateful 1988 World Series at-bat. / Courtesy of Yahoo Sports. |

That personal style has narrated some of baseball’s most memorable moments, making them more iconic in the process. Perfect games by Don Larsen at Yankee Stadium in the 1956 World Series, and by Sandy Koufax against the Chicago Cubs in the 1965 World Series; Hank Aaron’s 715th career home run to surpass Babe Ruth’s record in 1974; Fernando Valenzuela’s no-hitter in 1990; Barry Bonds’ record-shattering home runs in 2001. If you ask him, Scully will tell you his trademark is knowing when to “shut up” and let the moment happen. The moment I remember most vividly was when I was only four-years-old, but when my Dad was a prime 39. It was Game 1 of the 1988 World Series at Dodgers Stadium. The Dodgers were playing the Oakland A’s, who were leading 4-3 when Kirk Gibson limped off the bench to pinch-hit with two outs in the 9th inning. After multiple foul balls, the count goes to three-and-two...and then a crack of the bat. “High fly ball into right field, she is gone,” Scully says before the mic goes silent for more than a minute. During this silence, Gibson hobbles round the bases, pumping his arm in exhausted ecstasy, and is swarmed by his teammates. Scully returns to say: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.” Obviously I was too young to actually remember that moment, but, growing up in Dodgerstown, I saw it replayed ad infinitum. Now, without listening to the audio, I can instinctively hear Scully’s inflections on “she is gone” because that moment doesn’t exist without his poignant, tenor commentary. I can also see my Dad pumping his arm like Kirk Gibson as he so often did when savoring a personal victory. This kind of flagrant celebration drove us all nuts, but, in hindsight, it was just my Dad identifying as an injured pinch-hitter making a clutch play against all odds. That’s the beauty of Vin Scully’s baseball: he enables us to see ourselves in the players, and identify with outcomes on the field.

When Kirk Gibson launched that home run into the bleachers, it descended into Dodgers lore and brought Vin Scully along for the ride. He’s so synonymous with baseball because of moments like these that it’s hard to envision him outside the Dodgers announcer’s booth, but his career was not limited to one sport. From 1969-1970, he hosted a game show called It Takes Two, as well as a short-lived weekend afternoon variety show, appropriately called The Vin Scully Show, in 1973. He called play-by-play for NFL games and PGA Tour events for CBS from 1975-1982. I was surprised to learn that Vin Scully does not watch baseball games that he does not call, because he simply has too many other interests, like literature and Broadway musicals. Although still within the realm of baseball, he called World Series’ and All-Star Games, appeared in Kevin Costner’s For the Love of the Game, and provided voiceovers for a Playstation MLB game.

|

| The iconic broadcaster as host of The Vin Scully Show, 1973. / Courtesy of CBS Photo Archive. |

Vin Scully is beloved personally and professionally because of his work ethic, his moral compass, and his humility in addition to what he believes is his God-given talent. He has an impressive list of awards to his credit, and California has rightfully recognized him as one of its own. He has been named California Sportscaster of the Year over 20 times. In 2008, he was inducted into the California Sports Hall of Fame, and, that same year, a bronze plaque was installed by the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission in Memorial Court which reads: “The games are ephemeral, the scores are forgotten, the players come and go, but the emotions endure, and the contributions of Vincent Edward Scully to Los Angeles will last forever.” This year, Dodgers Stadium’s main entrance street was renamed Vin Scully Avenue from Elysian Park Avenue so that future generations will always associate him with the Chavez Ravine, even if his voice no longer echoes within it. Despite these accolades, Scully has remained remarkably humble; he said: “All my career, all I have ever really done, all I ever have accomplished, is to talk about the accomplishments of others. We can’t all be heroes. Somebody has to stand on the curb and applaud as the parade goes by.”

|

| My Dad’s last Dodgers cap, which now hangs in the entryway of my apartment. / Courtesy of Nicole Meldahl. |

I came of age under the distant but watchful eye of Vin Scully, as did the generation before me. Dependable commonalities like Dodgers dogs and Scully’s soothing tenor voice help unite us during times of economic uncertainty, political polarity, and worldwide humanitarian crises. California might be a vast expanse of competing cultures, but Vin Scully is a piece of California history everyone can agree on--even Giants fans; he is the tie that binds. It’s truly hard to imagine baseball without him, and I’d bet it’s hard for Scully to imagine himself without baseball. My Dad fills the room every time I hear Vin Scully call a baseball game; I treasure him for that, because that feeling is fleeting, it’s precious. The further we get from my Dad’s life the less lifelike he becomes, but tangible connections to the time we had with him, like Scully, stay the unending process of grief...even if it’s only for nine innings. Similarly, the job that Scully has executed to perfection for so long helped him through the tragic deaths of his first wife and his son. At his first game back following the dismal 1994-1995 strike season, Scully said: “After being away, I’ve come to the realization that I need you more than you need me.” With all do respect, Mr. Scully, you’re wrong; the truth is we’ve needed each other equally all these years. Thank you for allowing us to pull up a chair.

|

| Vin Scully at in his announcer’s booth at Dodgers Stadium, September 25, 2016. / Photo by Chris Carlson, AP via El Paso Times. |

Vin Scully’s final call will happen today at 12:05 PST. KNBR and CSN Bay Area will air his broadcast of the 3rd inning so Giants fans can be distant witnesses to history. Otherwise, Dodgers friends in Los Angeles can watch the broadcast on KTLA or listen on AM 570. Those of us outside the region can listen through iHeartRadio or something similar.

By Nicole Meldahl

Sources not hyperlinked in text:

- “Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story” by Curt Smith

- Recording of Helen Dell, longtime Dodgers Stadium organist.

- “Dodgers-Giants rivalry full of big moments on the verge of adding more in 2016” by Jonah Keri, 17 August 2016

- “Giants-Dodgers best rivalry in baseball” by Jim Caple

- “Vincent E. Scully, Class of 1944”, Fordham Preparatory School Hall of Honor

- “Vin Scully is a Legend, But He’s Not a Saint” by Keith Olbermann

- “A fond farewell to Vin Scully” by Samuel Chamberlain

- “The Rare Vin Scully” by Gregory Orfalea

- “Vin Scully Credits a Terrible Stadium and the Transistor Radio” by Richard Horgan

- “Vin Scully reflects on 67 years of baseball memories” by Beth Harris

- “The Man. The Voice. The Stories.” by Jayson Stark

No comments:

Post a Comment