One hundred and fifty years ago, the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in North America signaled the closing of the American frontier and the ability to travel from coast to coast quickly and with more ease than ever before. In recognition of this anniversary, the California Historical Society (CHS) presents two simultaneous exhibitions that examine the history of the railroad in California and beyond: Mark Ruwedel: Westward the Course of Empire and Overland to California: Commemorating the Transcontinental Railroad. Last week all of us at CHS had the pleasure of celebrating the opening of these two exhibitions with our members, VIP guests, and staff!

In his series Westward the Course of Empire (1994–2008), photographer Mark Ruwedel documents the physical traces of abandoned or never completed railroads throughout the American and Canadian West. Built in the name of progress as early as one hundred and fifty years ago, these now defunct rail lines are marked by visible alterations to the landscape. Ruwedel catalogues eroding cuts, disconnected wooden trestles, decaying tunnels, and lonely water towers in quietly powerful images that point to the contest between technology and the natural world. Using a large-format view camera, Ruwedel treads the same territory as nineteenth century survey photographers, but his contemporary perspective brings a sense of loss to landscapes once viewed as exploitable resources.

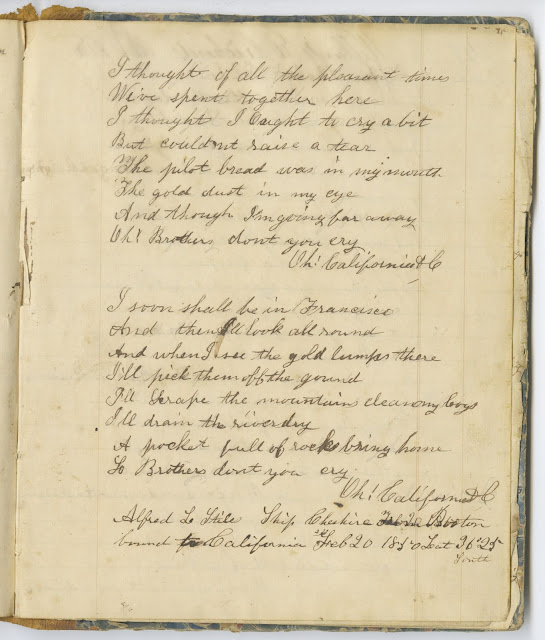

Overland to California: Commemorating the Transcontinental Railroad draws from the California Historical Society’s vast archival and photographic collections to consider the railroad’s impact on the industry and culture of California. Featuring photographs, stereocards, historical objects, and ephemera, this exhibition explores how the major railroad companies used marketing images to bolster their reputations and promote their lines in a period of rapid growth and social unrest. Overland to California will also examine the railroad’s complex labor history, taking into consideration the immigrant populations who built its infrastructure, as well as the scandals surrounding the monopolistic practices of the so-called “Big Four” railroad executives: Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins.

The exhibition features important archival material from CHS’s permanent collection including a mammoth plate photograph by Carleton Watkins of a helix-shaped stretch of track known as the Tehachapi Loop, as well as a first edition copy of Frank Norris’ 1901 novel, The Octopus. Also being exhibited on select viewing days is a 9.25 ounce gold spike, the last to be driven into the railroad that connected Los Angeles and San Francisco on September 5th, 1876, thereby joining Los Angeles to the East Coast. The spike was donated to CHS by an heir of railroad magnate Charles Crocker in 1956. It will be on view during special events throughout the exhibition.

Overland to California: Commemorating the Transcontinental Railroad draws from the California Historical Society’s vast archival and photographic collections to consider the railroad’s impact on the industry and culture of California. Featuring photographs, stereocards, historical objects, and ephemera, this exhibition explores how the major railroad companies used marketing images to bolster their reputations and promote their lines in a period of rapid growth and social unrest. Overland to California will also examine the railroad’s complex labor history, taking into consideration the immigrant populations who built its infrastructure, as well as the scandals surrounding the monopolistic practices of the so-called “Big Four” railroad executives: Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins.

The exhibition features important archival material from CHS’s permanent collection including a mammoth plate photograph by Carleton Watkins of a helix-shaped stretch of track known as the Tehachapi Loop, as well as a first edition copy of Frank Norris’ 1901 novel, The Octopus. Also being exhibited on select viewing days is a 9.25 ounce gold spike, the last to be driven into the railroad that connected Los Angeles and San Francisco on September 5th, 1876, thereby joining Los Angeles to the East Coast. The spike was donated to CHS by an heir of railroad magnate Charles Crocker in 1956. It will be on view during special events throughout the exhibition.

Last Thursday night's opening included remarks by Managing Curator, Erin Garcia, as well as CHS’s Director of Library, Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs, Susan Anderson. Food was provided by Straw Carnival Fare, with refreshments from Fort Point. Guests also enjoyed jazz by Francis Wong and Karl Evangelista.

Westward the Course of Empire and Overland to California will remain on view at CHS’s headquarters at 678 Mission St. in San Francisco until September 8, 2019. Please visit californiahistoricalsociety.org or call us at 415 357-1848 for more information.

Want to hang out with us at fun history events like this one? Join today!

Images courtesy of Shannon Foreman photography

Images courtesy of Shannon Foreman photography