Children’s Voices in the Archives is a series of posts brought to you by CHS’s North Baker Research Library. Stay tuned for more charming examples of history through a child’s eyes in the coming months.

Alfred Stiles’ diary reads like a mini adventure novel written from the perspective of a 13-year-old boy traveling from Boylston, Massachusetts on a ship headed to the Golden State. His sharp prose and keen observations may surprise you, not to mention his recording of details that veer into the journalistic then make a sharp turn towards the poetic. You might not think there would be much to do or observe on a ship’s long journey from Boston to San Francisco by way of Cape Horn (Dec. 1849 - June 1850), but even within the first few pages of Alfred’s diary, an avid debate club springs to life--the Cheshire Debating Club--to which his parents belonged. Alfred’s parents debated questions such as “Should the U.S. acquire the state of California?” Alfred diligently recorded the yeas and nays--his father in affirmative with 2 others and “Mother in Negative + 2 others.” They debated whether the acquisition of California would be of any benefit to the U.S.

Christmas and New Years did not go by without incident. Alfred notes some rowdy behavior on Christmas Day when “2 thirds of the passengers drunk besides Capt + mate + 1 or 2 hands the mate pulled Choate from port hand of the forecastle and struck him several blows on the head, when some of the passengers cried out ‘throw him overboard’” he left for his cabin. Amidst the blows and drink, Alfred reports they had 2 pigs for dinner and apple duff.

On New Years, “About 2 clock a man had 4 bucket served at his head and a few other things which created a great excitement.” One diary entry records Tuesday, January 1st 1850 as evincing a light breeze and people wishing each other a happy New Year, with some passengers wishing to have a Heigh ride at home while it is as warm as July. Next Alfred describes fresh pork and apple pie for dinner, as well as doughnuts for supper with the addition of black fish.

We also find moments of quiet admiration and reflection where whale watching upon the ship Cheshire reminds the reader of Moby Dick. Alfred writes in another entry, “Thursday dec [?] very sick passengers most all sick saw some whales about 3 miles off” then on the opposite page of the diary, the lone word Whale crowns the page of text like a chapter title.

On a separate entry, we find a lovely poem titled “A Life on the Ocean Wave,” where Alfred transforms into a caged eagle amidst scattered waters and a dull unchanging shore. [See end of blog for poem transcription]

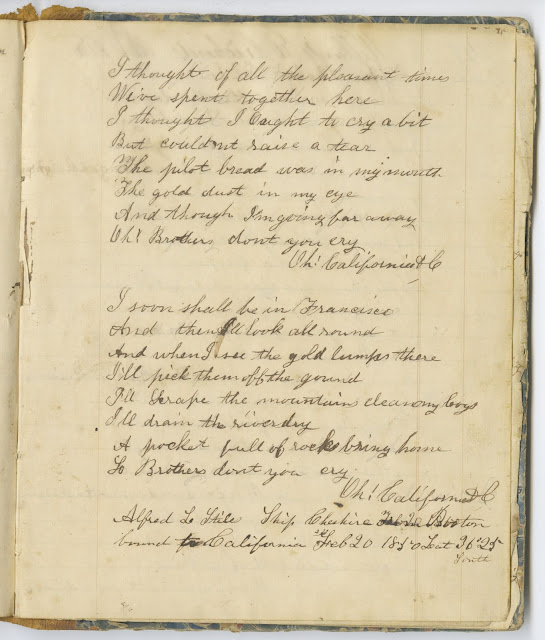

Some pages turn to odes yearning to find wealth in California, followed by a nostalgic homecoming. In the first stanzas Alfred reminisces upon pleasant times spent with loved ones, then the promise of “gold dust” in the eyes. This follows another line in which the writer waxes poetic about soon reaching San Francisco and fulfilling the fantasy of seeing “gold lumps there” on the streets ready for picking “off the ground,” as if the streets were lined with gold nuggets to fill one’s pockets full of riches to return home in glory.

Reading Alfred’s diary, whether you are an adult, teen, or child, will take you on an adventure from East to West Coast during a time when the promise of safe harbor in a new land might be your heart’s desire.

Poem Transcription for “A Life on the Ocean Wave”

A Life on the Ocean wave !!!!

A life on the Ocean Wave

A home on the rolling deep

Where the scattered waters save

And the Winds their [revels] keep

Like an Eagle caged I pine

On this dull unchanging shore

Oh! Give me the flashing Brine

The spray and the tempests roar

Once more on the deckd hand

Of my own swift gliding craft

Set sails farewell to the land

[May] the gale follow far aloft

We shoot through the sparkling foam

Like an Ocean Bird set free

Like an Ocean Bird our home

We find far out on the sea

The land is no longer in view

The clouds have begun to frown

But with a stout Vessel and Crew

We’ll say let the Storm come down

And the song of our hearts shall be

While the sounds and the waters save

A life on the heaving Sea

A Home on the bounding Wave !!!!!!

Alfred L. Stiles Ship Cheshire April 24, 1850

From Boston Bound to California

Transcription of Odes of yearning to California

I thought of all the pleasant times

We’ve spent together here

I thought I ought to cry a bit

But couldn’t raise a tear

The pilot bread was in my mouth

The gold dust in my eyes

And though I’m going far away

Oh! Brother don’t you cry

Oh! California

I soon shall be in San Francisco

And then look all around

And when I see the gold lumps there

I’ll pick them off the ground

I’ll scrape the mountains clearing logs

I’ll drain the river dry

A pocket full of rocks bring home

Lo Brothers don’t you cry

Oh! California

Alfred L. Stiles Ship Cheshire

Alfred Stiles’ diary reads like a mini adventure novel written from the perspective of a 13-year-old boy traveling from Boylston, Massachusetts on a ship headed to the Golden State. His sharp prose and keen observations may surprise you, not to mention his recording of details that veer into the journalistic then make a sharp turn towards the poetic. You might not think there would be much to do or observe on a ship’s long journey from Boston to San Francisco by way of Cape Horn (Dec. 1849 - June 1850), but even within the first few pages of Alfred’s diary, an avid debate club springs to life--the Cheshire Debating Club--to which his parents belonged. Alfred’s parents debated questions such as “Should the U.S. acquire the state of California?” Alfred diligently recorded the yeas and nays--his father in affirmative with 2 others and “Mother in Negative + 2 others.” They debated whether the acquisition of California would be of any benefit to the U.S.

|

| Cover page, 1847; Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1856; MS 4014; California Historical Society. |

|

| Passenger list, 1849-1850; Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1856; MS 4014; California Historical Society. |

On New Years, “About 2 clock a man had 4 bucket served at his head and a few other things which created a great excitement.” One diary entry records Tuesday, January 1st 1850 as evincing a light breeze and people wishing each other a happy New Year, with some passengers wishing to have a Heigh ride at home while it is as warm as July. Next Alfred describes fresh pork and apple pie for dinner, as well as doughnuts for supper with the addition of black fish.

We also find moments of quiet admiration and reflection where whale watching upon the ship Cheshire reminds the reader of Moby Dick. Alfred writes in another entry, “Thursday dec [?] very sick passengers most all sick saw some whales about 3 miles off” then on the opposite page of the diary, the lone word Whale crowns the page of text like a chapter title.

|

| Whale title heading, 1849-1850; Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1856; MS 4014; California Historical Society. |

|

| “A Life on the Ocean Wave” poem, 1850; Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1856; MS 4014; California Historical Society. |

|

| Odes “Oh! California,” 1850; Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1850; MS 4014; California Historical Society. |

Poem Transcription for “A Life on the Ocean Wave”

A Life on the Ocean wave !!!!

A life on the Ocean Wave

A home on the rolling deep

Where the scattered waters save

And the Winds their [revels] keep

Like an Eagle caged I pine

On this dull unchanging shore

Oh! Give me the flashing Brine

The spray and the tempests roar

Once more on the deckd hand

Of my own swift gliding craft

Set sails farewell to the land

[May] the gale follow far aloft

We shoot through the sparkling foam

Like an Ocean Bird set free

Like an Ocean Bird our home

We find far out on the sea

The land is no longer in view

The clouds have begun to frown

But with a stout Vessel and Crew

We’ll say let the Storm come down

And the song of our hearts shall be

While the sounds and the waters save

A life on the heaving Sea

A Home on the bounding Wave !!!!!!

Alfred L. Stiles Ship Cheshire April 24, 1850

From Boston Bound to California

Transcription of Odes of yearning to California

I thought of all the pleasant times

We’ve spent together here

I thought I ought to cry a bit

But couldn’t raise a tear

The pilot bread was in my mouth

The gold dust in my eyes

And though I’m going far away

Oh! Brother don’t you cry

Oh! California

I soon shall be in San Francisco

And then look all around

And when I see the gold lumps there

I’ll pick them off the ground

I’ll scrape the mountains clearing logs

I’ll drain the river dry

A pocket full of rocks bring home

Lo Brothers don’t you cry

Oh! California

Alfred L. Stiles Ship Cheshire

From Boston Bound to California Feb. 20, 1850 Lat 36 25 South

--

Written by Lynda Letona, Assistant Archivist & Reference Librarian at California Historical Society (CHS).

Photos digitized by Marissa Friedman, Imaging Technician and Cataloger at CHS.

Reference:

Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1850; MS 4014; California Historical Society.

--

Written by Lynda Letona, Assistant Archivist & Reference Librarian at California Historical Society (CHS).

Photos digitized by Marissa Friedman, Imaging Technician and Cataloger at CHS.

Reference:

Alfred L. Stiles diary and letter, 1849-1850; MS 4014; California Historical Society.