|

| Group of Chinese Children, 1909 California Historical Society |

Over 130 years ago today, the United States passed legislation discriminating against Chinese immigrants. The Chinese Exclusion Act, approved May 6, 1882, drew from nearly four decades of anti-Chinese sentiment, especially in California. With its passage, people of Chinese descent seeking work in the United States could not enter the country for 10 years. The act also increased restrictions against Chinese immigrants already living in the United States.

The Chinese Exclusion Act—our nation’s first law banning immigration on the basis of race and nationality—marked the beginning of a 60-year era of Chinese exclusion litigation. As some historians have pointed out, it “helped to shape twentieth-century United States race-based immigration policy.”

|

| George Frederick Keller (Illustrator), “The First Blow at the Chinese Question,” San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, December 5, 1878 Courtesy of Thomasnastcartoons.com |

Between 1850 and 1870, about 8,000 Chinese arrived in California annually. They found jobs building the railroads and working in agriculture, manufacturing, and industry. To white California workers, they and other low-wage minorities were a source of resentment, prejudice, and racial discrimination. “The Chinese Must Go” became the motto for workingmen political parties and associations.Initially intended for Chinese laborers, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended in 1888 to include all persons of Chinese descent. In California, anti-Asian sentiment actually began decades earlier. During the Gold Rush, from 1849 to 1852, around 25,000 Chinese arrived in California, remaining here to work in mining and other businesses.

Even after the Gold Rush ended, the number of Chinese immigrants continued to grow. In 1854, the number arriving in San Francisco was four times as many as had arrived just the year before. Racism and discrimination exploded as Chinese laborers were accused of taking jobs away from Americans. By the depression decade of the 1870s, the anti-Chinese movement was marked by violence and wide-ranging political influence.

|

| English-Chinese Phrase Book, 1875 Published: Wong Sam and Assistants, English-Chinese Phrase Book Together with the Vocabulary of Trade, Law, etc. (San Francisco: Cubery, 1875) Courtesy Wells Fargo Archives |

This English-Chinese phrase book was distributed for free to new immigrants at Wells Fargo offices throughout the West. According to one historian, its “wide range of vocabulary and phrases concerning harsh working conditions, violence, persecution, and death reveals why ‘a Chinaman’s chance’—meaning ‘no chance at all’—became a familiar saying throughout the West and what kind of justice the Chinese could expect. It proved indirectly that even before anti-Chinese sentiment gained momentum in the late 1870s, mistreatment of Chinese had already become common on the West Coast.”

|

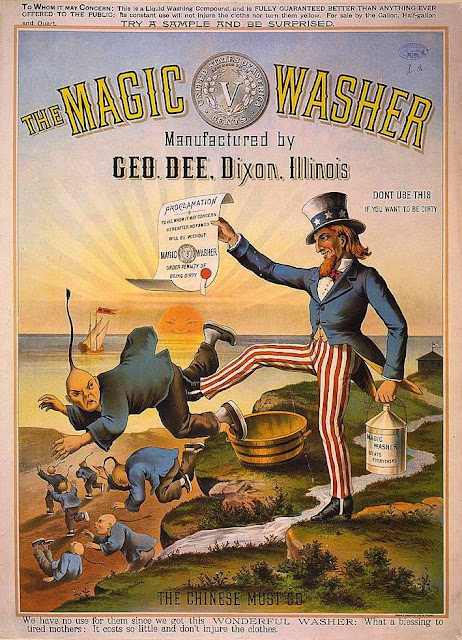

| The Magic Washer / The Chinese Must Go, c. 1886 Library of Congress |

This advertisement for a new washing liquid exploited the nation’s anti-Chinese sentiment to sell its product. Targeting the primarily Chinese laundry trade, it proclaims “The Chinese Must Go. We have no use for them since we got this Wonderful Washer.”

The situation worsened on May 5, 1892, when Congress passed the Act to Prohibit the Coming of Chinese Persons into the United States. Known as the Geary Act after California Democratic congressman Thomas J. Geary, this new law extended the 1882 act, prevented further immigration for another ten years, and required that Chinese laborers carry certificates of residence to confirm their legal status.

|

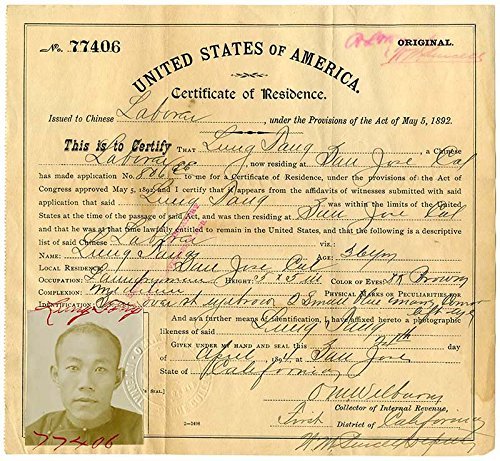

| Certificate of Residence for Lung Tang, Laundryman, Age 36 Years, of San Jose, California, April 24, 1894 Certificates of Residents for Chinese Laborers, MS 3642, California Historical Society |

Under the provisions of the 1892 Geary Act, all Chinese in the United States were required to apply for, obtain, and carry a government-issued certificate of residence proving their legal presence in the United States. Chinese and Chinese Americans found without such identification could be arrested and deported. California’s certificates required the laborer's name, local residence, and occupation; information about his height, eye color, complexion, and physical marks or peculiarities; and a photographic print. The one above is signed and stamped by O. M. Welburn, Internal Revenue Collector, First District of California.

Unlike for any other group of nonresidents, the Geary Act required that Chinese laborers obtain a certificate of residence by May 5, 1893, one year after the act’s passage. Protests about the act’s unconstitutionality led all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Through such organizations as the Chinese Six Companies, San Francisco’s Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the Chinese American community protested the Geary Act. In September 1892, the Chinese Six Companies organized a successful campaign of resistance among all 110,000 Chinese immigrants in the United States. Red circulars urged them to disobey the “Dog Tag Law” and refuse to register for certificates of residence on grounds of the law’s unconstitutionality. The Companies also hired attorneys to challenge the law before the U.S. Supreme Court, in Fong Yue Ting v. United States. On May 15, 1893, the Court ruled in favor of the Geary Act, a decision that would impact immigration hearings for Chinese and non-Chinese alike for years to come.

In 1902, the Geary Act was made permanent. It was finally repealed in 1943, along with other Chinese exclusion laws still in effect, with passage of the Magnuson Act. In 1965, the legacy of the exclusion acts came to an end when the Immigration and Nationality Act eliminated racial classifications from the law.

|

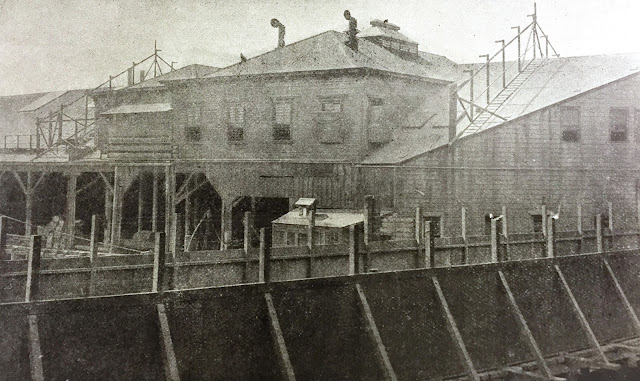

| Caption, “Herding Coolies from the Coptic into the Detention Sheds of the Mail Dock” San Francisco Call, May 12, 1900; California Digital Newspaper Collection |

Detention Sheds of the Pacific Mail Dock Swarm with Chinese from the Steamer Coptic screamed the San Francisco Call headline on May 12, 1900. As the Call’s reporter observed: “Scores after scores of coolies were marched from the deck of the ship to the detention shed until 191 had passed down the gang plank on to American soil, where they will remain not temporarily but indefinitely.” The unsympathetic reporter added, “The Pacific Mail dock is perhaps the most important dock on the Pacific Coast. Enormous quantities of freight and thousands of passengers pass through it every month. Above the heads of the passengers are these ill smelling coolies.”

Chinese immigrants arriving by steamship into the Port of San Francisco—even those exempt from the exclusion laws, such as prior U.S. citizens returning from visits to China—via the Pacific Mail Steamship Company were detained at this two-story makeshift detention shed on the Pacific Mail Steamship Company wharf. Up to 500 were kept at the inadequate and unsanitary facility until federal immigration inspectors determined their admissibility—sometimes days or weeks later. Protests about the conditions led to the establishment of Angel Island Immigration Station in 1910.On June 5, 2014, the California State Senate passed a resolution apologizing for anti-Chinese legislation and calling for a formal apology from the U.S. Congress. On July 17, 2009, the California legislature approved a landmark bill of apology to the Chinese American community for the Chinese Exclusion Act, with plans to ask Congress to do the same.

|

| Hung Liu (artist), Resident Alien, 1988 http://www.hungliu.com/resident-alien.html |

Artist Hung Liu’s resident alien card is part of a series of paintings interpreting the history of Chinese immigration to California, 1848–1988. In it, she adapts her own dated green card under the pseudonym Fortune Cookie.

Shelly Kale

Publications and Strategic Projects Manager

skale@calhist.org

Sources

Publications and Strategic Projects Manager

skale@calhist.org

Sources

- Iris Change, The Chinese in America (New York: Penguin Group, 2003)

- We-Wui Chung Chen, “Changing Social-Cultural Patterns of the Chinese Community in Los Angeles, PhD dissertation, University of Southern California, 1952

- Erika Lee, “The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882–1924,” Journal of American Ethnic History 21, no. 3 (Spring 2002); http://web.uvic.ca/~ayh/Lee.pdf

- Ling Woo Liu, “California Apologizes to Chinese Americans,” Time, July 22, 2009; http://content.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1911981,00.html

- Lucy E. Salyer, Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995)

- Wong Sam and Assistants, An English-Chinese Phrase Book Together with the Vocabulary of Trade, Law, etc. (San Francisco: Cubery, 1875); http://herb.ashp.cuny.edu/files/original/engchinesephrasebook_d947664841.pdf

- J. Thomas Scharf, LL.D., Late United States Chinese Inspector at the Port of New York, The Farce of the Chinese Exclusion Laws (1898); http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=4055

- Paul Yin, “The Narratives of Chinese-American Litigation During the Chinese Exclusion Era,” Asian American Law Journal 19 (2012); http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/aalj/vol19/iss1/6

- Xiao-huang Yin, Chinese American Literature Since the 1850s (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000)

No comments:

Post a Comment