|

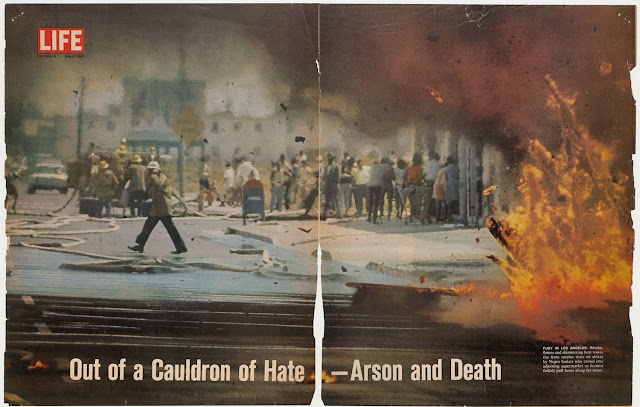

Arson and Street War, Life magazine, August 27, 1965

Courtesy California ephemera collection, UCLA

Library Special Collections

|

Fifty

years ago, from August 11 to 17, 1965, a community was shattered. A city was torn

apart. Property was destroyed. Lives were lost.

The

Watts Riots in Los Angeles—to some a riot, to others a rebellion—were set off

by the arrest of a black drunk driver and the altercations that followed. While

the McCone Commission’s investigation rooted the turmoil in inequality,

poverty, and racial discrimination, a 1970 Institute of Government and Public

Affairs survey of almost 600 Watts-area residents cited poor neighborhood conditions, mistreatment by whites, and

economic conditions.

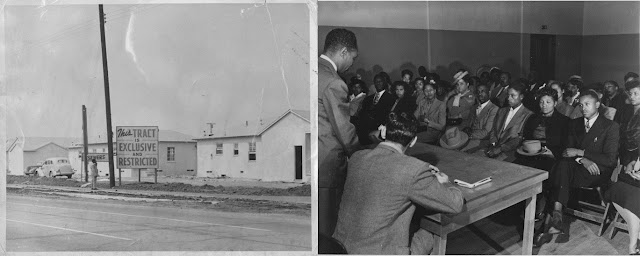

The

Watts section of South Los Angeles had been a predominantly working-class black

community since the 1940s, when tens of thousands of African Americans migrated

from the South for better opportunities in California. Within a couple of

decades, the area was beset by overpopulation, poverty, segregation, and

unemployment.

Nationally,

the 1964 passage of the Civil Rights Act—outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin—and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 offered promise of a new direction in

race relations.

But in California,

as elsewhere in the country, progress was slow—a source of frustration and

despair. In 1964, Californians voted to overturn the Rumford Fair Housing Act,

enacted the year before to grant equal opportunity for black home buyers. In Watts,

whose population by 1965 was 87 percent African American—the most segregated city in

the West—tensions were already high.

Over six days of rioting, 34

people died, 1,000 were injured, and more than 4,000 were arrested. Businesses

were looted and destroyed, incurring a loss of about $200 million. As 14,000

thousand

National Guard troops, along with the California Highway Patrol and local law-enforcement

officers, imposed a strict military curfew, the nonviolence

of the Civil Rights Movement came to a close.

|

Aerial view of burning buildings, August 13, 1965; Library of Congress

|

(Left)

Soldiers of California’s 40th Armored Division in Watts, 1965; courtesy

National Guard Education Foundation; (right)

Three National Guardsmen stand guard under a Los Angeles city limits sign in

the southern end of the riot-torn section of the city, 1965; Library of

Congress

Ceremony of Us: A Multiracial

Response

For three years

following the Watts Riots, similar violence erupted in other American cities:

Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Newark. Watts, in contrast, sought and accelerated

self-organized community projects to bring solutions to social problems. One,

the Studio Watts School of the Arts, headed by James Woods, provided leadership

training to youths through the arts.

In WATTS: Art and Social Change in Los Angeles,

1965–2002, Elliott Pinkney describes the studio’s intent— “The

project provided for some 150 students training in visual arts, music, drama,

dance, and writing”—and its manifesto: “We must facilitate the individual’s

regaining an awareness of himself as an instrument of change. Studio Watts

Workshop supports a cultural democracy to deal with the broad scope of social,

technical, and economic problems.”

In San Francisco, another response to the

political and social change of the sixties was occurring in the workshops led

by the avant-garde dancer Anna Halprin, known today as a pioneer in the expressive

arts healing movement. Seeking to explore issues of race, in the summer of 1968

Halprin received an invitation from Woods to work with African Americans in

Watts and create an original work about the process.

|

Promotional image for Ceremony of Us, 1969; photo: Susan Landor Keegin

|

Instead, she offered to develop an

all-black company at Studio Watts and an all-white one in San Francisco and to produce

a multiracial performance based on the experience. She worked with each group

separately and then brought them together for a ten-day rehearsal prior to the

scheduled performance. Ceremony of Us premiered

on February 27, 1969, at the Los Angeles Music Center following five months of

discovering “who we are in relationship to blacks and whites,” as Anna later

explained in her book Moving Toward Life:

Five Decades of Transformational Dance (1995). “We started out being scared

to death of each other. And curious. It’s hard to believe this but . . . this

was the first time that this particular group from Watts had ever been in any

kind of an intimate relationship with a group of white people. And vice versa."

Among the many exercises into

personal exploration Halprin introduced to the Watts group was one she had

implemented in Experiments in Environment,

a multidisciplinary workshop series she co-developed with her husband,

landscape architect Lawrence Halprin: a blindfolded walk through the

environment. While the exercise into personal exploration failed with the Watts

group, the studio performers continued on a personal “healing process.”

|

As Janice Ross has written in her

biography Anna Halprin: Experience as

Dance (2007), the Ceremony of Us workshop

brought Halprin “a fresh understanding of how complex and layered the

interweavings of each individual’s political, racial, and cultural history are

in the performance work.” The next summer Halprin held multiracial workshops

“in which she probed these issues and tested means for doing what she now felt

was her raison d’être as an artist—‘trying to connect dance with people’s

lives.’” With funding from the National Endowment of the Arts’ Expansion Arts

Program, Halprin initiated Reach Out, a multiracial dance ensemble.

Describing her current work in

community building, personal healing, and world peace in 2009, the now

95-year-old Halprin wrote in her foreword to Anna Halprin: Dance, Process, Form (2015), “Now more than ever in

my lifetime, I see the need to redefine dance once more as a powerful force for

transformation, healing, education, and making our lives whole, a dance that

will speak to our needs today.”

|

Anna Halprin with dancers from the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop and

Studio Watts School for the Arts, during a rehearsal for Ceremony of Us, 1969. Courtesy of Anna Halprin.

|

Anna and Lawrence Halprin’s Experiments in Environment workshop series, mentioned above, is a

focus of the California Historical Society’s current exhibition

and events project Experiments in Environment .

Shelly Kale

Publications and Strategic Projects Manager

Further Reading: Choreographing the Environment: The Counterculture of Anna and Lawrence Halprin, by Shelly Kale, July 13, 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment